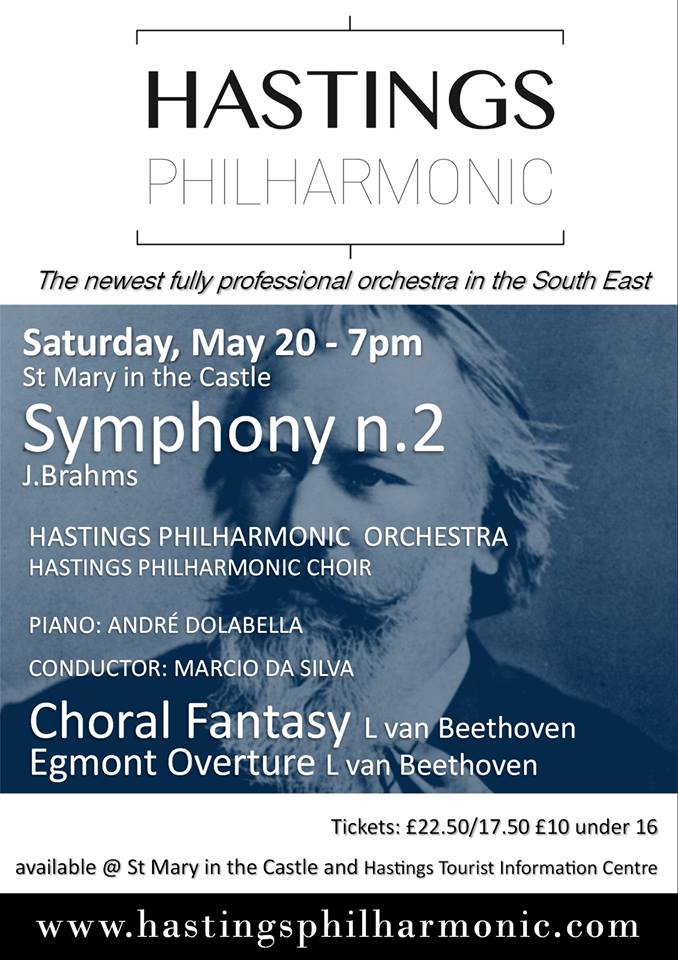

Hastings Philharmonic is producing a keynote concert which shows off its full professional orchestra to best effect. The concert of Beethoven and Brahms are at St Mary in the Castle on Saturday 20 May at 7pm. In addition to Beethoven’s Egmont overture and Brahms’ 2nd Symphony, the concert features a rare choral, orchestral and piano piece by Beethoven which was a precursor to his ninth (choral) symphony.

Beethoven’s Choral Fantasy Op 80 was composed late in 1808 as a concert finale that incorporated elements of several works from an extraordinary concert. The concert included premieres of some of Beethoven’s finest works: Beethoven presented for the first time his 6th (Pastoral) Symphony,his 4th Piano Concerto in G major (with Beethoven himself as soloist), the 5th Symphony, ‘Ah Perfido’, ‘Gloria’ and ‘Sanctus’ (from his C major mass); Beethoven played the piano part himself in the first part of the Fantasy for piano, chorus and orchestra and it ended triumphantly.

Far from being a slick affair, the Choral Fantasy’s composition and performance is thought to have been a last minute concoction, but it served as a precursor to Beethoven’s Choral Symphony No.9; Beethoven had not written a score for the piano solo at the beginning and extemporised at the premiere on 22 December 1808 in Vienna. Improvisation was not unusual and even expected of virtuoso musicians in Beethoven’s time. Consequently the actual piano score now used owes something to a reworking nearly a hundred years later by the famous late 19th century pianist Xaver Scharwenka. The concert made Beethoven more famous than ever and proved his greatness after a less than well received Fidelio put on earlier that year had dashed his hopes .

Beethoven’s pupil, Carl Czerny, wrote that the Symphony in c minor (his 5th) was meant to conclude the concert but to delay this important symphony to the end would have lessened its impact after so many other worthy new pieces. According to Czerny, Beethoven felt this and, at the last minute, wrote a separate finale. He chose a song that he had composed many years before, sketched out a few variations, the chorus, etc, and the poet Kuffner was commissioned to write a choral text. The result was the Choral Fantasy, Op. 80.

The first two thirds of the work is a somewhat unusual concert piece for piano solo and orchestra; it begins with an expansive solo passage almost as if it were a piano sonata.Then the orchestra joins in and only later does the chorus enter with some melodic elements of “Ode to Joy” – which was to be completed as the Choral Symphony some 15 years later.

Although not a poet of Schiller’s stature, Christoph Kuffner’s poem used for the Fantasy bears the hallmarks of many Age of Enlightenment writings and the post-revolutionary ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity. Beethoven’s possible membership of the freemasons is still a very controversial topic, but the case for his being one is based partly on the statement by his later personal secretary and admirer, musician Karl Holz, that he had been a mason but was inactive in later life.

Roger Cotte in his book La Musique Maçonnique suggests that Beethoven’s Fantasia Op 80 was indeed a masonic work describing it as a ‘veritable symphonic poem on initiation of the first degree’. Cotte suggests that the unusual structure of this piece reflects a masonic initiation ceremony: it starts with the initiate standing in darkness represented by the long piano introduction. As the initiates are unveiled, the interaction between orchestra and piano represents the question and answer phase, while a horns, oboe and piano passage concludes the unveiling and leads to the choral climax. The choral jubilation was, according to Cotte, steeped in masonic symbolism both in words and music with the text ‘When love and strength are united, the favour of God rewards man’ being closely associated with the masonic concept of moving from Dark to Light, and a c minor-major progression of the music being evocative of a leap towards joy.

One of the highlights of the concert is Brahms’ great 2nd Symphony which should be a delight coming from the full romantic Hastings Philharmonic Orchestra The concert at St Mary in the Castle also includes Beethoven’s Egmont overture, music set for Goethe’s ‘Sturm und Drang’ drama which was dripping in revolutionary ideals of the late eighteenth century. Goethe’s membership as a mason was fully documented.

Hastings Philharmonic Orchestra play Brahms 2nd Symphony, Beethoven’s Choral Fantasy and the Egmont Overture at St Mary in the Castle, 7 Pelham Crescent, Hastings TN34 3AF on Saturday 20 May at 7pm. Tickets £22.50, £17.50 and £10 (under 16s)