BBC Symphony orchestra and chorus

Barbican Hall, 15 May 2015

With all the commemorations for the First World War I cannot recollect any recent performance of Sir Arthur Bliss’ Morning Heroes, first heard in 1930 as a memorial not only to the dead as a whole but in particular to his own brother, and a reflection on his own suffering on the Somme. With its striking choral settings, pitched somewhere between The Kingdom and Belshazzar, and its sumptuous orchestration you might have expected a large number of choirs to have taken it up but it appears not to have happened. All the stranger when one considers the impact of the work in the concert hall.

Perhaps it is the need for a strongly focussed orator? Here the BBC had marshalled the services of Samuel West, whose incisive and virile tones proved to be ideal for the passages from the Iliad and the more introspective notes of Wilfred Owen. The choral setting is demanding but not over-complex, allowing the text to carry with ease. Unlike Britten, Bliss is constantly aware of the allure of warfare. For all that men die, they are attracted to the bombast and pageantry of the build-up, and the excitement of attack. It is the women for whom there is great sensitivity, whether it be Andromache in the opening section or the poignancy of the warrior’s wife in Li Po’s Vigil.

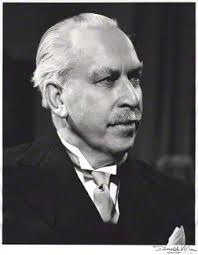

Sir Andrew Davis has a deep commitment to British choral music and proved this yet again, convincing us that this is a work which can stand alongside any of the great works of the twentieth century.

This would have been enough for most listeners in itself but the concert had opened with two works by Berlioz. The Royal Hunt and Storm from The Trojans is familiar, but rarely in concert do we have the privilege of a full chorus for the height of the storm. It was splendid!

Then came La mort de Cleopatre. Is there anyone better in this work today than Sarah Connolly? I recall Janet Baker singing it many years ago with electrifying impact but this was in another league altogether. It also proves that a great singer can simply stand and sing to convey the intensity of the score, without any need for histrionics or semi-staging. Her careful crafting of the text, the sense of emotional melt-down, was impeccably controlled to the point where she dies before our eyes – a moment of real pathos and great beauty.

The concert is available via the Iplayer for 30 days but given the quality I would hope the works will be released on CD for posterity – they certainly deserve it.