Wormsley, 1 July 2015

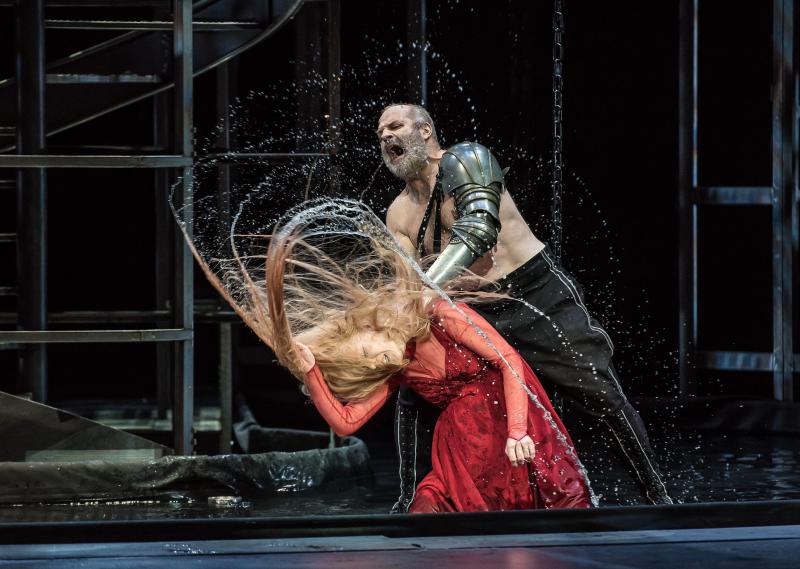

The vast drifting, billowing white curtains of Kevin Knight’s setting create the perfect environment for Paul Curran’s insightful and sensitive re-appraisal of Britten’s final masterpiece. More than any recent production I can recall we are constantly made aware of Aschenbach’s isolation. Though he is surrounded by the life of La Serenissima it passes in an instant from sharp reality to hazy memory. There are many telling moments – the crowd reading the cholera notices, Tadzio walking past oblivious because distanced by the change of light through the curtain, hotel guests so close yet outside Aschenbach’s world. More than anything else this puts the whole focus of the work firmly on Paul Nilon’s Aschenbach and he brings us a man of intense humanity and passion, attempting to make sense of his creative life but always on the brink of collapse, just as life in Venice is itself about to go down under the tide of cholera. His voice has weight and a fragile authority which reflects the changes of mood with ease and the many moments of pain and exquisite beauty. It is the heart of the work but he is fortunate to be surrounded by so fine a company for the myriad of smaller parts.

Because the work is conceived within a dreamlike world, the dancing seems to make a bigger impact. There is no sense of dream sequences, more a case of Aschenbach moving in and out of memory. As a consequence it is easier for us to take all the dancers seriously as a normal part of Aschenbach’s world rather than an addition to it. In this Celestin Boutin is particularly successful as Tazio. He presents us with a very real young man – at least in his late teens – who is as open to a heterosexual interest in the Governess as he is to larking about with his friends. The very normality of his Tadzio makes Aschenbach’s infatuation all the more striking.

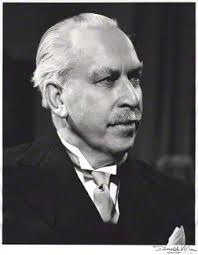

The other key performer is William Dazeley’s shape-shifting Traveller, ever present to undermine Aschenbach’s flights of fancy. His changes of costume and personality are subtle enough to confuse and accurate enough to combine all of them into the antagonist that Aschenbach finds so difficult to confront.

The large cast of characters are drawn from strength and while many are necessarily rapidly pencilled stereotypes, the production manages to keep them convincingly naturalistic. As ever the Garsington Chorus provide fine voices and real presence.

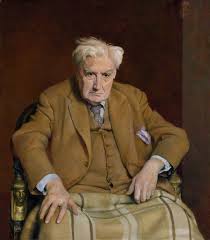

Holding the whole evening together is Steuart Bedford’s masterly control of the glorious nuances of Britten’s orchestral writing. He conducted the first performance in 1973 at a time when the composer was too ill to conduct himself. It was the only work to have been mounted without the direct involvement of the composer himself and in many ways has a closer association with Steuart Bedford than any other. Garsington Opera are privileged to have his experienced hand on the tiller for a production which, yet again, speaks of the growth of this company as far more than a summer opera.